Best Practice Blog: Risk Management & Crisis Communication

By Race Director, Shane Ohly

Look out for our series of articles about good practice in adventure sports events. We hope that other organisers will find these articles useful and thoughtful, whilst also providing insight for our participants about the background operations at our events.

If you enjoy reading this, perhaps you’d like to join us at the annual Adventure Sports Events Conference where race organisers get together to learn from each other and subject matter experts.

Introduction

Most race organisers have an intuitive sense of the risks involved in their event because they are participants themselves. In this short blog, I wanted to explore how effective risk management and crisis communication can be used to prevent an accident from becoming a disaster.

Whilst the type of events organised by Ourea Events are not ‘large’ by festival standards they are often complex, held in austere mountainous environments and have the potential to be highly consequential for the participants (and event staff). The same can be said for many other mountain running and adventure sports events, and I am writing this blog in the hope that other event organisers will find it useful for the safe planning and delivery of their own events. The graphics within this blog come directly from our internal Crisis Communications Plan.

Background

In addition to the challenging environments that adventure sports events take place, they are also subject to the standard emergency and crisis risks faced by other events such as extreme weather, cancellation, terrorism, and other such incidents. No amount of preparedness can mitigate against all potential random events and possible incidents, which could overwhelm the embedded event resources such that they threaten the safety of any individual involved in the event, risk financial losses to the business and/or jeopardise the good reputation of the business and/or the event stakeholders. In summary, a crisis can risk:

Personal Safety

Financial Loss

Reputational Damage

Emergencies, Crisis, Disasters: What is the Difference?

There is no universally accepted definition agreeing on the differences between Emergencies, Crises and Disasters. For the purposes of this blog, I’ll define them according to Borodzicz (1999) summarised in the following table (green sections):

Another way of understanding disasters is that, “Disasters do not cause effects. The effects are what we call a disaster." Wolf Dombrowsky (1995). Interesting you might say, but what are the practical implications of this on an adventure sports events organiser? We do not plan for the management of ‘disasters’ as an event incident of that magnitude will already be out of our hands and managed by the statutory emergency services and authorities. However, we do considerable planning, combined with significant investment in the resources so that we are able to recognise, and then manage an emergency in the earliest possible phase so that it does not escalate into a crisis. For example:

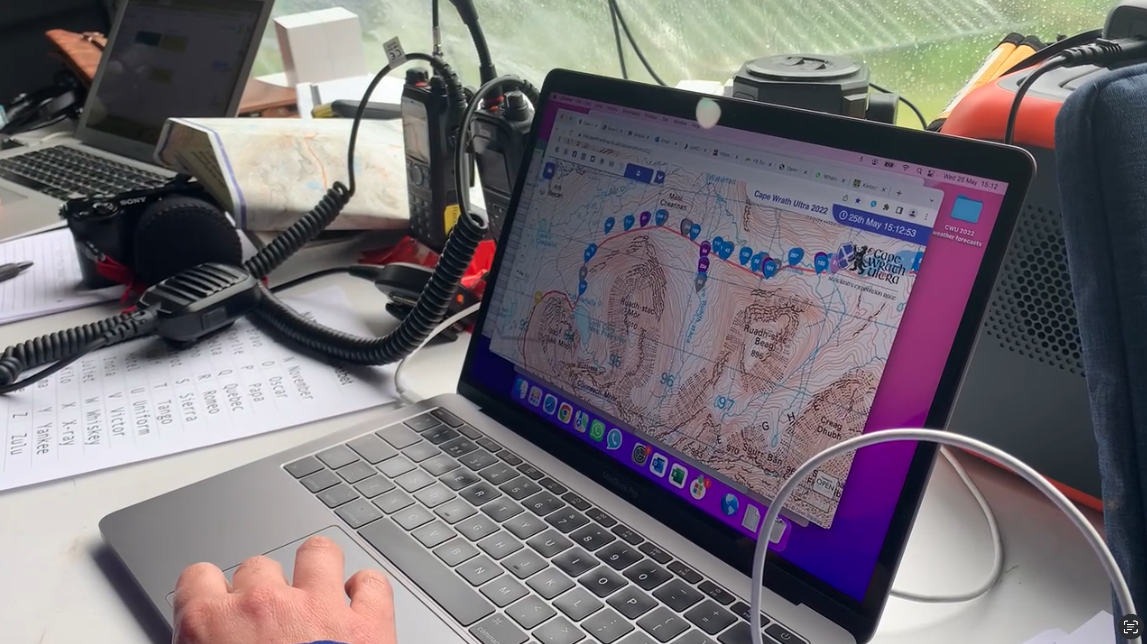

Command, Control and Communication (C3) systems. This means a clearly defined hierarchy and system for managing information and decision-making, combined with the ability to affect those decisions with communications and tracking systems that enable us to talk with and follow staff deployed on the hill.

Procedures. Robust rules for each event include classics like ‘minimum mandatory clothing and equipment’ and a zero-tolerance approach to anyone disobeying our event rules and procedures.

Competence of Staff. Ensuring that all professional and volunteer staff are competent for the role they undertake by considering a blend of each individual's competency, experience, qualifications and education. As it’ll be your event team doing work such as kit checking at registration, marshalling a checkpoint, and recording participants safely finished and therefore it is important to ensure that the right person is doing the right job.

Staff competency is critical for the roles allocated. In this picture, we feature one of the two Response Teams operating at 2021 Montane Dragon’s Back Race®. From left to right: Dave (Mountain Rescue Team Leader), Fern (SARDA Search Dog), Tom (Mountain Rescue Team Doctor and Dan (Mountain Rescue Team Member and Student Paramedic). © No Limits Photography

How an Emergency becomes a Crisis

Simplistically, a crisis is an unmanaged emergency. In the following table, you can follow the development of an emergency (such as an injured runner becoming stationary on your race route) through the different prodromal, acute, chronic and recovery phases that characterise the pathway of unmanaged or ineffectively managed emergencies.

Haverfordwest Paddleboarding Disaster 2021

If you would like to review a formal accident investigation into the Haverfordwest paddleboarding disaster in October 2021, which resulted in four fatalities, have a read of the Marine Accident Investigation Branch report. The classic ‘Swiss Cheese Accident’ alignment of various factors during the prodromal phase is evident throughout the report.

Emergencies and Crisis: Mitigation Strategies

A well-managed event with good pre-planning and preparedness should be able to manage routine emergencies predictable at their particular type of event, and significantly reduce the chance of a crisis developing. The threat of a crisis developing can be reduced by the following CONTROL MEASURE principles:

Monitoring: Effective safety management systems help prevent an emergency from becoming a crisis.

Prodromal Phase: Experienced event managers can see, and manage, precipitating events whilst it in the prodromal phase.

Communication: Without effective communication methods across the event it is impossible to manage/change anything!

Contingency Planning: Robust contingency planning and preparedness helps prepare the event for the unexpected.

Emergency Services: The early involvement of the statutory emergency services and authorities.

Emergency Response

It is important to understand that ‘business as usual’ has ceased once an emergency has occurred and a crisis threatens. At this stage, there must be sufficient resourcing, capability and focus within the event management team to respond to the initial emergency so that it does not escalate, whilst also continuing to effectively manage everything else concerned with the ongoing event.

We prepare for significant emergency situations because of the nature of our events, and the long response times of the statuary emergency services. Whilst Ourea Events is not a statutory “Category 1 responder” (such as the 999 emergency services) as described by Civil Contingencies Act 2004, the business does fulfil this initial role at our events with the provision of our in-house medical and Response Team. Of note, is that the Police have increasingly recognised the capability of our Response Team and deployed them directly to incidents rather than the local Mountain Rescue team.

Scenes from the 2022 edition of the Cape Wrath Ultra® feature two separate rescues. The first row of photos shows Response Team 1 evacuating a participant with a lower leg fracture on day one. The third row of photos shows Response Team 2 preparing for the helicopter evacuation of a profoundly hypothermic participant on day four. The middle row is our Race Control team coordinating the rescue shown in the third row of photos (video HERE). © Stuart Smith and ©Shane Ohly

Mitigation Strategies

Davies (1998) “Concludes that organisations can become crisis-prepared, if they adopt a range of strategies, such as providing good feedback on previous incidents, setting up a formal safety organisation, inculcating safety culture norms and beliefs about the importance of safety, devolving decision making but retaining monitoring by experienced staff, training and educating to create an environment of constant awareness and hence reliability. The end product should be that those unpredictable everyday minor crises do not escalate to become disasters”.

A thorough kit check takes place at registration before the start of the 2022 Cape Wrath Ultra® ©No Limits Photography

For Ourea Events some of the mitigation strategies are practical (such as a mandatory equipment list for participants), others rely on an experienced Race Control team (their ability to interpret marginal weather conditions) and some are process driven (the emergency protocols contained within the Event Safety Management Plan). Each of these mitigation processes is a control measure that when combined one after the other create formidable barriers to accidents occurring, emergencies developing and crisis resulting.

The original ‘Swiss Cheese Accident’ model was proposed by Dante Orlandella and James T. Reason (Reason, 1990) and is widely used in aviation safety and risk management. Inspired by Orlandella and Reason, the following ‘Combined Mitigation and Cumulative Effect Model of Event Incident Management’ graphic seeks to illustrate how multiple mitigating control measures reduce risk, whilst the ‘perfect’ combination of events can still combine to cause the emergency that leads to a crisis:

Crisis Communications

The management and communication around event emergencies and crisis is something that we want to take a proactive approach to, and our Crisis Communication Plan focuses on our preparedness for this. The plan provides go-to checklists, background context and general preparedness for senior Ourea Events staff to refer to whilst managing the communication around a crisis incident. It is essential that a senior member of staff (Race Director or Event Director) act as the company’s representative in all official interactions with the media (press conferences, press briefings etc.). In the modern age of social media, 24-hour news and citizen journalism it is important that swift, decisive, open and honest action to address any crisis head-on is taken. The key principles are:

Who says it: SENIOR MEMBER OF STAFF

What is said: BE HONEST, BE CLEAR, BE CONCISE

When it is said: BE FIRST

Why?

It is well established that the absence of information during a crisis is likely to lead to increased reputational damage and consequently financial loss for the organisations linked to the crisis. Therefore, crisis communication “seeks to explain the specific event, identify likely consequences and outcomes, and provide specific harm-reducing information to affected communities in an honest, candid, prompt, accurate, and complete manner” (Reynolds and Seeger, 2005).